As someone who works with both marketers and developers, I’ve noticed a stark difference in their mentalities.

Frequently, marketers will say “my ads aren’t working,” without much thought put into why. Perhaps it’s the conversion funnel. Perhaps it’s the messaging in their ads. Marketers usually aren’t sure, and they’ll aimlessly throw darts at the wall until something sticks.

Developers are different. When code isn’t working, they home in on the root cause, then debug the issue. They don’t throw darts at the wall.

Let’s take a look at how to use numerical data from your e-commerce funnel to find out why campaigns aren’t profitable, then utilize one of the two strategies to fix them

- Playing to Win

- Playing not to Lose

The phrases above are borrowed from sports.

Playing to Win means acting more aggressively when your team is losing to (or neck-to-neck with) an opponent. Playing Not to Lose means playing conservatively when your team is sufficiently ahead.

It’s the difference between “Let’s f^ck shi* up” (shi* being the opposing team) vs. “Let’s not f^ck up.” (Unless you’re the Jets and play “not to lose” even when you’re losing.)

An Example E-Commerce Funnel

Let’s take a look at the funnel of a product (we’ll call this Product A) in the health and nutrition space:

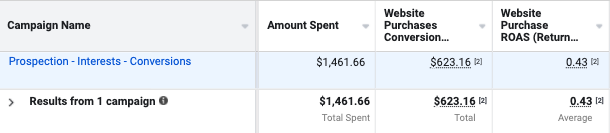

This account has spent $1,461.66 to get $623.16 back, for a RoAS (i.e. Return on Ad Spend) of 0.43.

Put another way, this campaign made $0.43 for every $1 spent. Yikes.

So, how does one increase this number? Improve creative/copy on ads that are running? Find a better audience? Change the optimization goal on the ad platform from Purchase to something like Add to Cart?

This is where most marketers throw darts at the wall and try all of the above.

But there’s a better, more systematic, way to approach this. Let’s take a look at the underlying funnel metrics.

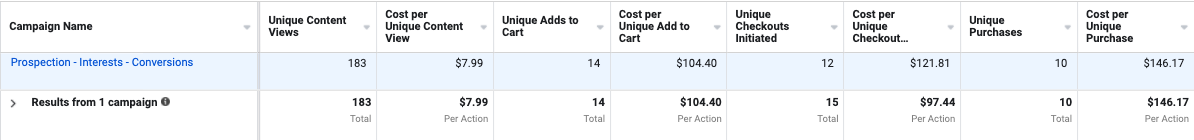

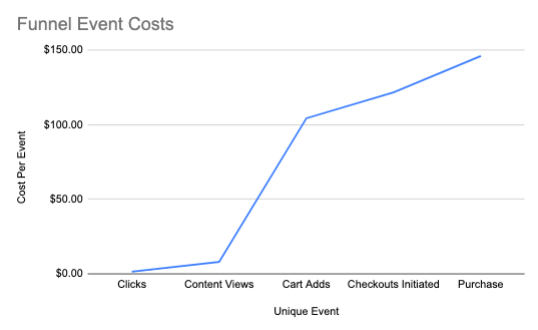

The metrics above show each step of the funnel along with associated costs.

There were 10 purchases, meaning that the CAC (i.e. Customer Acquisition Cost) of this campaign was $146.17. We can also calculate AOV (i.e. Average Order Value) by dividing total conversion value ($623.16, from the first image) by the total purchases, which yields $62.32.

We have a few key metrics to look at now:

- AOV: $62.32

- CAC: $146.17

- Cost per Unique Cart Adds (i.e. Add ToCart) event: $104.40

The last metric, cost per “Unique Cart Add” (CUCA) is extremely crucial, because of the importance of the “Add to Cart” event.

CUCA: The Diagnostic E-Commerce Metric

CUCA is important, because it is the very first indication that someone has seen a product’s value proposition, its price, and has an intent to purchase.

The example above uses Facebook’s ad platform, but this metric is platform agnostic; it’s an important e-commerce event irrespective of acquisition channel.

By the time a user has shown an intent to purchase in the funnel above, their associated cost (i.e. $104.40) is larger than its AOV.

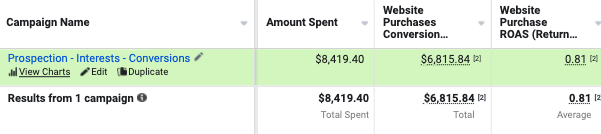

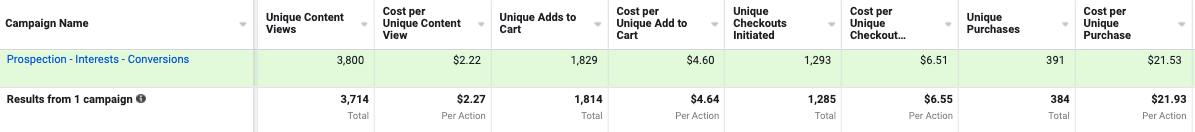

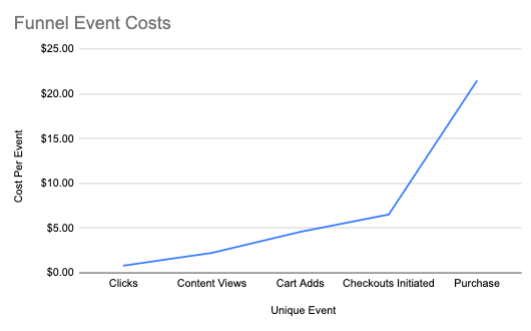

Now, take a look at a different e-commerce funnel (a monthly subscription box), which also has a RoAS below 1.0. We’ll label this Product B.

Its underlying metrics are as follows:

Here, the CUCA is $4.80, which is dwarfed by the relative AOV ($17.43). Instead, the largest relative increase in costs occurs from Initiate Checkout to Purchase events.

So, how does CUCA dictate what you should do to fix this funnel?

When CUCA is relatively high relative to AOV, you haven’t sufficiently convinced a user to buy your product; the price of your product is either too high or you have not given potential customers enough of a reason to move forward.

In this case, you need to focus on “Playing to Win.” You haven’t won the user’s attention and interest yet, so you need to do what you can to aggressively (relative to the second strategy, which we’ll get to shortly) court your would-be customer’s interest.

The name of the game here is selling to the customer to increase their propensity to purchase. Let’s call this “buying temperature” for shorthand. A high buying temperature means users are primed to purchase, whereas a low buying temperature means they lack interest.

When CUCA is low relative to AOV, but RoAS is not sufficiently adequate, buying temperature is sufficient. However, for some reason, users second guess their decision before completing a purchase. Maybe there’s an additional shipping cost that they didn’t consider, or perhaps they’re worried that the product won’t work as described.

Here, as is the case with Product B, your focus should be “Playing Not to Lose.” You already have a potential buyer’s attention–you need to focus instead on reassuring the customer to encourage them to go through with their purchase.

Here, as is the case with Product B, your focus should be “Playing Not to Lose.” You already have a potential buyer’s attention–you need to focus instead on reassuring the customer to encourage them to go through with their purchase.

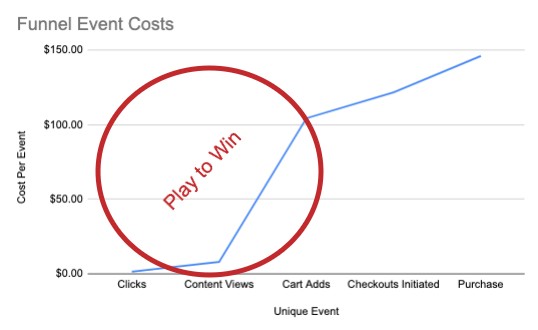

Playing to Win

Let’s take a look at a graph showing Product A’s average customer costs as we make our way down the funnel.

A graph like this screams “increase buying temperature.”

There are several ways you can do this, but for brevity’s sake, we’ll list the most effective tactics.

- Consider lowering your price.

Buying temperature isn’t just a function of value…it’s also a function of price.

Let’s take a step back and ask a very basic question: What makes someone purchase a good or service?

A customer purchases an item when its perceived value is sufficiently high relative to its price. In economics, the difference between a good’s perceived value and the price is known as consumer surplus, and people inherently seek to maximize said surplus.

This means that you can achieve this not only by increasing perceived value, but also by lowering the price.

Anecdotally, when it comes to selling something online, there seem to be certain “breakpoints” in which CAC increases disproportionately to an increase in price. These breakpoints go something like:

- $0 to $40

- $41 to $80

- $81 to $120

- $120 to $150

- $150+

In other words, hypothetically cutting a $50 product’s price by 30% (i.e. to $35) might yield a decrease in CAC of more than 30%.

Calculate your breakeven RoAS and AOV, then test pricing your product somewhere between there and your existing price. You can also retarget people along your funnel with various discounts in order to create the same effect for specific users in your funnel.

- Add an aggressive sales lander

Most people run acquisition to a generic homepage, which is fine for pre-qualified channels, such as referrals, organic traffic, and search traffic.

However, many marketers make the mistake of acquiring users from social networks like Facebook, TikTok, Pinterest, etc., then expecting them to be “sold” by a generic homepage.

Consider creating a landing page using something like Instapage, which you use for paid media traffic.

Marketers are often scared of being too aggressive when it comes to making sales pages, but this fear is usually overblown. Targeting by relevant interests or utilizing a lookalike audience will create a higher threshold for more aggressive direct marketing.

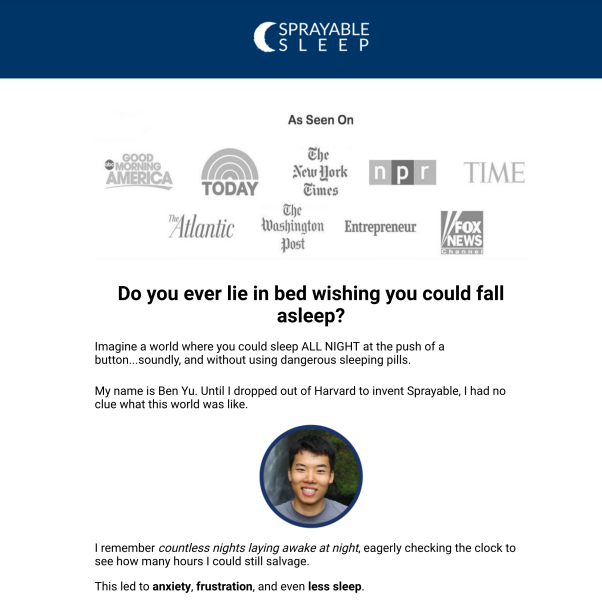

Here’s an example of one of the top performing sales pages I’ve written, which converted 5-10% of global cold traffic. You don’t need to make your sales page as aggressive as this, but you do need to sell to your customer.

- Hook the user within their first few seconds.

You need to do everything that you can so that you hook a user within moments of viewing your site (or better yet, you can drum up buying temperature in your ad).

Here’s a user’s first glimpse of the example lander I linked above:

Notice the immediately visible “As Seen On” section above, as well as the question being posed. (“Why yes…yes I do sometimes wish I could fall asleep!”)

Try to get into the mindset of a prospective, unqualified, customer.

They clicked on an ad, not knowing very much about your product. They’re probably distracted, clicked out of pure curiosity, and probably not in “purchase” mode. If you don’t play to win by hooking them hard from the get-go, you’ll likely lose them.

- Sell benefits, not features.

Lastly, make sure you’re focusing on features, not benefits. Inventors often make crappy marketers, because they take pride in features they created (understandably so) while neglecting their actual benefits.

Users don’t give two shits if your product is sustainable, organic, non-GMO, etc. At least not in-and-of themselves. Their ears will perk up, however, if it will help them lose weight, make more money, or fix a pain they have right now.

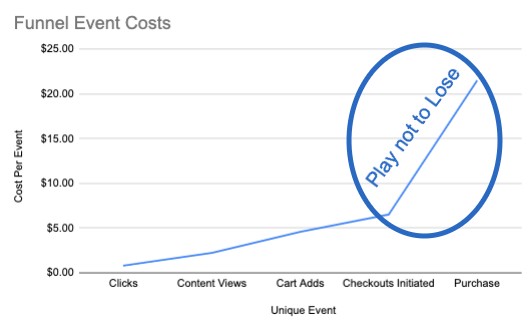

Playing Not to Lose

Let’s take a look at the graph of Product B’s funnel.

Seeing an exponential increase in CPA after CUCA indicates that your strategy needs to be “Playing Not to Lose.” Something is spooking customers from completing a purchase.

It’s worth noting that this is on par for the course. No conversion rate from checkout to purchase is ever going to be 100%. In fact, 50% is generally acceptable, if not good in many cases.

Here are a few things to consider:

- Checkout conversion rate is negatively correlated to product price. You shouldn’t be concerned if your checkout conversion rate is 30% for a $1,000 product…a $30 product is a different story.

- Subscription purchases will generally cut checkout conversion rate in half, if not more.

The name of the game here is to alleviate any concerns that might give customers cold feet. Here are some of the top tactics you can utilize:

- Decrease funnel friction (bugs, additional steps, etc).

You want to do everything that you can to decrease friction between a visitor showing purchase intent and the actual purchase. While obvious, this remains the top culprit I’ve seen in e-commerce funnels.

Make sure you minimize the number of steps it takes to complete a purchase (e.g. don’t force the user to create an account), check for checkout/cart bugs, and reduce overall friction.

- Incorporate social proof.

You need to show potential customers that others have bought your product and are satisfied.

Consider including a testimonial section in your sales page or somewhere between your product page (when a user adds an item to their cart) and checkout, without adding additional friction.

You can also add reviews/ratings somewhere that the user can find. People who have second thoughts will often click around your site looking for reasons to purchase (or not to purchase), so there’s no need to muddy up your funnel.

- Add a FAQ.

Same reasoning as above.

- Eliminate last-second costs as best as possible.

Cart abandonment often occurs when there’s an unexpected last second cost, such as shipping or taxes. Consider adding free shipping if users spend a certain amount, then building this cost into the cost of the item. This will both let the user know ahead of time that there’s a shipping cost, as well as

- Manage your Google search presence.

People will often do their research after they add an item to their cart, because the reality of the impact to their wallet hits them. If they run a Google search on your product, make sure that they like what they’re going to find.

And there you have it. Hopefully, you’ll approach a broken funnel in a much more systematic, analytical way. Much like anything else, e-commerce funnels are an iterative process–but there needs to be a process before you can iterate.